|

| Corduroy dad hat from Rowing Blazers. |

Q: Do you feel like traditional men’s style has an image problem?

Jack Carlson: Well, that depends on what you mean by "traditional men's style." The Trad Police... which can be found spewing thinly disguised racism on message boards and in the Ivy-Style comments section - a load of Archie Bunkers in blue blazers - don't do themselves any favors. More broadly, "traditional men's style" has an image problem in that those purveying it usually present it poorly. It isn't marketed well, and how else can one define "an image problem"?(1)Sometimes a Dad Hat Is Just a Dad Hat (but Not When It's From J. Press)

The other day, Rowing Blazers - the clothing company founded by Dr. Jack Carlson, PhD (why does no one ever call him this?), former United States rowing medalist, author of the book Rowing Blazers, and Person Who Attended Oxford - shared this Medium post, titled "J.Crew, Rowing Blazers, and The Decline of Prep...," by a guy named Clayton Chambers, on their Instagram. Now, my point in discussing Chambers's post is not to rip him, or it, apart. I don't know who he is, even. However, I disagree with Chambers's main argument, and I think that his argument, and my disagreement with it, unearths something interesting about Rowing Blazers and its place in the current (eternal) debate over preppy clothing and its place in American culture.

First, some quick background on preppy clothing (for best results, read the next paragraph very fast). Preppy clothing has its roots in the boxy, loose-fitting No. 1 Sack Suit, the striped repp tie, the odd jacket with a rolled-over top button, the oxford-cloth button down shirt, and the Weejun penny loafer. The foundational codifiers and marketers, in the 1920s and 1930s, of what was eventually known as the "Ivy" style, for its popularity on Ivy League campuses and among Ivy League graduates - Brooks Brothers in New York, J. Press in New Haven, G.H. Bass and L.L. Bean in Maine, et. al. - were themselves codified into establishment style in the 1960s, as Ivy-styled clothes were marketed in magazines like Playboy, written about in magazines like Esquire, and seen in movies starring the likes of Tony Randall, Tab Hunter, Paul Newman, Robert Redford, Anthony Perkins, Steve McQueen, Cary Grant, and so on. This establishment style fell out of favor in the late 1960s and early 1970s as college kids grew out their hair and rebelled against the Wall Street fathers who were paying for them to go to Kent State. It was then finally resurrected as a tongue-in-cheek, ironic aspirational elite style by Lisa Birnbach in The Official Preppy Handbook, first published in 1980. The Handbook, along with a slew of what I call "douchebags at private school" movies, revitalized Ivy style, now embodied by navy blazers, bow ties, pink Lacoste polos, boat shoes, and pants with things embroidered on them, as three things: first, clothes for rich assholes (see: Breaking Away); second, clothes for people who very much wanted to be rich assholes (see: Izod); and third, people who thought the rich assholes and the people who wanted to be them were hilarious. Get all that? Good. (Oh, and you can stop reading fast.)

I believe that Rowing Blazers was founded in a spirit of deep sincerity and earnestness. Carlson, as mentioned earlier, is a former United States rowing medalist and Person Who Attended Oxford. In 2014, he combined these two passions into the book Rowing Blazers, an exhaustive look at the history of the rowing blazer, i.e. the original navy blazer. Carlson came by this project through an earnest interest in the history and traditions of the sport he loves, and through serious scholarship as a PhD student studying

Our FW19 collection is inspired by the desire to cling to youth and the inevitability of "growing up," whatever that means: early adulthood’s mix of melancholy and excitement in all its nostalgic forms - Yuppie culture, identity crises, and a longing to go “back to school.” Films like St. Elmo's Fire - which takes place at RB founder Jack Carlson's alma mater, Georgetown - and series like Friends (shout out to "The One With All The Rugby") capture this spirit, as well as the zeitgeist of a seemingly simpler time, when the stakes were low and the world was young.

The collection - drawing on these '80s and '90s cultural moments in both attitude and style - is not just post-Ivy in the sense that it reflects a post-collegiate or post-graduation ethos, however. Post Ivy is also a play on Take Ivy - the (contrived, idealized) Japanese anthropological study of American campus culture in the late ‘50s that many since then have taken as a style bible. But in 2019, we believe that classic American collegiate style transcends narrow, and in any case artificial, categorizations like "Ivy style," and beyond the baggage that comes with these constructs and labels. Collegiate, by definition, is the intersection of traditional and youthful - and youth culture - a youthful sense of irony and irreverence - is as important an inspiration to this collection as the staged photos in books like Take Ivy.I'm going to come back to this blurb later, so bear with me. But before I move on, I want to emphasize that I like Rowing Blazers. I own several things from them, and am happy to support a brand that is putting out a younger, fresher, more inclusive picture of clothes that have been almost totally reserved for the white elite, or the aspiring white elite, for pretty much their entire history (find a person of color in The Official Preppy Handbook. I'll wait[3]). In 2018, New York Times music and culture critic Jon Caramanica wrote of J. Press that its store windows "reminded [him] largely of wealth I didn’t have, rooms I would never be allowed into. Rooms I had to convince myself weren’t worth craving.... I’d pop into J. Press mostly to look, little doses of class tourism." Caramanica doesn't end up buying an oxford shirt or a pair of Aldens - instead, he chooses "a corduroy baseball cap":

It was floppy and unstructured, a dad hat made for actual dads. The way it sagged suggested wealth around long enough to have heated, and then settled, like the earth itself. I was trying on the green one when the clerk informed me there was a pink one as well. I couldn’t decide between the two, so I got both.Dad hats! Called such by cool young people who wear ugly and dorky "dad hats" and "dad sneakers" ironically, making them cool in the process. A humble cap that, made by J. Press in soft corduroy (the most dadly of fabrics?), also symbolizes wealth (and old wealth, the most elite kind of wealth). Caramanica rejects the clubby, square world of Ivy and preppy style, but he buys pink and green caps, the colors championed by the Official Preppy Handbook ("the wearing of the pink and the green is the surest and quickest way to group identification within the Prep set") and many a "douchebags at private school" movie in the 1980s, or in other words, the most canonical preppy colors you can find. The J. Press dad cap Caramanica likes both upends and reinforces the class system he finds uncomfortable. In other words, he would love Rowing Blazers.(4)

There Are Only Two Known Cures for The Prep Disease: Reincarnation or Bankruptcy

So. To come back to Clayton Chambers and the Medium post that started this whole thing. The article's main purpose is to address the bankruptcy of J. Crew - if you actually want to learn about this and what could be done about it, click here to read Michael Williams's thoughts at A Continuous Lean - but Chambers spends most of his time extolling the virtues of Rowing Blazers, which he positions as a symbol of the vitality of "prep as an ideal" in contrast to the death of "prep as a signal of wealth." Now, there are some obvious issues with this position. First, Rowing Blazers is an expensive brand, all things considered. A flagship blazer costs around $1,000, their Bishop madras jacket costs nearly $700, and even a blazer with less frills, like their terry cloth beach blazer, is $325; their ties, which are made in England or New York, are between $80 and $150 dollars; that Quarantine University t-shirt is $42. You can easily argue, then, that Rowing Blazers is just as much "prep as a signal of wealth" as Brooks Brothers or J. Press. It's more complicated than that, though, because Chambers is talking about an "ideal," something to be aspired to. Let's put our quibbles over cost to one side, and say that Chambers is essentially arguing that the value of Rowing Blazers as an ideal of prep transcends the value of Rowing Blazers as prep as a signal of wealth when thinking about its place in American culture, circa July 28th, 2020 ("Behind the financial struggles of brands like J. Crew and Brooks Brothers, there’s something we can all learn about the cultural shifts driving" the "decline of prep"). To quote Chambers more fully:

Rowing Blazers can repurpose prep + ivy style as an act of rebellion against wasp-culture, classism — legacy wealth in America.... Younger audiences crave this sense of identity in their style.... And it’s not the first time we’ve seen this happen with the old guard of American fashion. Hip-hop culture has long used Ralph Lauren as a center piece in their work, highlighting the irony + disparity of American classism.... Polo wasn’t meant for hip-hop culture. So they took it and made it their own. As an act of rebellion to the American dream. The same applies to J. Crew and Rowing Blazers. Both are aspirational. One is ironic. The other is not.Let's break this argument down a bit:

- The establishment is ripe for ironic repurposing. For example, Ralph Lauren repurposed the Brooks Brothers establishment in the 1980s, and when it became establishment was itself repurposed by hip-hop culture.

- This repurposing highlights the irony and the disparity of American classism. It serves as an act of rebellion against the American dream, an aspirational ideal that excludes many; its repurposing presents that ideal ironically, reducing its exclusionary power,(5) and it claims the original power for those who were excluded.

I was really happy to read this. Not because I agree - as I said at the start of this post, I don't - but because I finally realized that I might have an opportunity to talk about something I've wanted to talk about for a while, but haven't known how to. I'm talking about Rowing Blazers's many versions of the famous 1979 "Are You A Preppie?" poster. (Rowing Blazers actually sells this original poster for $10,000, if you're looking for a way to get rid of all that loose change you found the last time you cleaned the sheepskin seat covers in your Volvo 240DL.)

|

| The 1979 poster, from the Rowing Blazers website. Click for larger. |

Of course, the genius of the OPH, which pulled back the curtain on elite culture, was to reincarnate the powerless kid as the powerful one, to recast the establishment as the private club - not something to be hated or protested, but rather something to be infiltrated and crashed. And the crashers aren't the establishment - they're the underdogs. They're the poor, powerless kids who wear flood level pants to show the rich, powerful kids that they don't have a monopoly on the uniform of power. They aren't the preppy Rob Lowe in Class, they're the fish-out-of-water Andrew McCarthy. They're Philip Weiss at the Bohemian Grove. Of course, as far as anyone at the Bohemian Grove knew, Philip Weiss was supposed to be there. And at the end of Class, Andrew McCarthy has sex with Rob Lowe's mom. Ironic, outsider prep has a way of becoming sincere, insider prep. As Brian Roche writes about the mustache that Malcolm, Jack Black's character in Noah Baumbach's Margot at the Wedding, insists is "meant to be funny," "an ironic mustache is still a mustache." Ironic prep is still prep, after all.

What Sort of Man Wears Rowing Blazers?

Now, I can't refute Chambers's argument by defining what he calls the "ideal of prep," because that could mean many things to many people, and because Chambers doesn't define it in his post, I don't know what it means to him. However, as I described earlier, Chambers does discuss what he feels like Rowing Blazers does stand for. By representing prep ironically and irreverently, Chambers argues, Rowing Blazers highlights the issues of class in America, such as "legacy wealth" and exclusion. By being "ironic prep," Rowing Blazers repurposes prep as a signal of wealth, and gives it to... to....

Uh-oh. Who does Rowing Blazers give this repurposed prep to? This is obviously very important. To return to Chambers's Polo example - one could argue that Polo wasn't meant for Wall Street finance guys, but if they'd taken it and made it their own, would it have had the same effect as it being worn by the hip-hop community? Obviously not. Punching down isn't subversive, only punching up is. By "punching up" at Polo's depiction of Americana, prep included, hip-hop made that depiction cool. By "punching up" at dorky dad style, centennials make it cool. So who punches in Rowing Blazers, and in which direction? All Chambers says about Rowing Blazers's demographic is that it's "younger audiences." So where can we turn to find out about who is wearing this "ironic prep," and why?

Well, we can find out from Rowing Blazers itself. Chambers accurately describes Rowing Blazers as "aspirational," and every aspirational brand has to show its customers what they should be aspiring to be. Chambers describes Rowing Blazers as being aspirational in the sense of providing a sense of identity, one that punches up using irony - punching up at legacy wealth, classism, etc. In essence, Rowing Blazers is for the person who loves elite style, but who for any number of reasons - historical disenfranchisement, liberal politics, etc. - doesn't want the moral ickiness of elite wealth status. Does Rowing Blazers itself confirm this reading of its "ironic prep"?

There are so many aspects of the Rowing Blazers brand that could be used to help answer this question - from Jack Carlson's own Instagram profile (bio: "♣️ @rowingblazers founder / 🇺🇸 us national team alum / 🥉 world champs bronze medalist / 🎓 phd oxford / 🐶 hoyas /🏺archaeologist / 🍟 vegetarian") to @rbmoodboard, essentially an official brand identity account (recent posts include Slim Aarons, Babar, Princess Diana, Ferris Bueller's Day Off, and Jay-Z). However, I want to focus on one piece of their marketing in particular.

|

| The Rowing Blazers "Are You A Preppie?" Gimberly poster. Click for larger. |

1. Hasn't Spilled Anything on Pants (Ever)

|

| Model Camille Opp in a Rowing Blazers poster. From Instagram. |

|

| Model Curtis Fuhrmann in a Rowing Blazers poster. From Instagram. |

First, you're relatable. These two posters are both heavy on relatability, real or aspirational. In other words, they aren't about what the Rowing Blazers customer consumes, but rather about who they are - their taste, let's say. Cami Opp's fun shirt-wearing young woman goes to the Natural History Museum, has lost an airpod, and tends to spill things on herself. This establishes her as someone who at least visits New York City, and as absent-minded and a bit klutzy (this last point will be important later, so hold on to it). Curtis Fuhrmann's moody Francophile listens to obscure French hip-hop and American indie rock, and "had a crush on Mireille," the nipply blonde in Pierre Capretz's French in Action language-learning series (this will also be important later). All of this Francophilia is a bit pretentious, though - and the poster knows it. Obscure French hip-hop can be found in dozens of compilations on YouTube, and I assume our young man's study of Mireille was in preparation for his only actual experience of France, his year abroad. We've all known that one friend who couldn't get over their "life-changing" semester in Paris, right?

In Opp's poised young woman and Curtis's somewhat bashful guy (this, also, will be important), we get a sense of two sides of the Rowing Blazers ideal customer: both are youthful and photogenic, but Opp's character is more human, more flawed, more relatable, with an imminent trouser-stain, an interest in museums, and a habit of losing things, while Curtis's character is a bit more full of himself, more stuffy, listening to hipster music and speaking French. In these characters, Rowing Blazers gives us a portrait of ourselves that we can laugh at and aspire to be - one we can envy secretly (when was the last time you went to a concert? Do you speak French? And what about that VW Harlequin, the fun shirt of cars?) while telling ourselves we're actually better (still talking about that year abroad? And who do you think you're fooling with that vitamin gummy?).

Remember when I said I'd come back to that blurb from the Rowing Blazers website? Let's bring it back for a moment:

In Opp's poised young woman and Curtis's somewhat bashful guy (this, also, will be important), we get a sense of two sides of the Rowing Blazers ideal customer: both are youthful and photogenic, but Opp's character is more human, more flawed, more relatable, with an imminent trouser-stain, an interest in museums, and a habit of losing things, while Curtis's character is a bit more full of himself, more stuffy, listening to hipster music and speaking French. In these characters, Rowing Blazers gives us a portrait of ourselves that we can laugh at and aspire to be - one we can envy secretly (when was the last time you went to a concert? Do you speak French? And what about that VW Harlequin, the fun shirt of cars?) while telling ourselves we're actually better (still talking about that year abroad? And who do you think you're fooling with that vitamin gummy?).

Remember when I said I'd come back to that blurb from the Rowing Blazers website? Let's bring it back for a moment:

Our FW19 collection is inspired by the desire to cling to youth and the inevitability of "growing up," whatever that means: early adulthood’s mix of melancholy and excitement in all its nostalgic forms - Yuppie culture, identity crises, and a longing to go “back to school.”In these two posters, we get this idea illustrated: youthfulness, even immaturity; nostalgia for college life, if only in the meme-ified way that the '80s and '90s are celebrated in the internet (French in Action premiered in 1987); the melancholy of a carefree life spilling food on expensive clothes and losing expensive airpods and spending money on concert tickets that most adults can't afford to indulge in.

2. American-Made Madras Patchwork Dad Hat (Not Actually His Dad's)

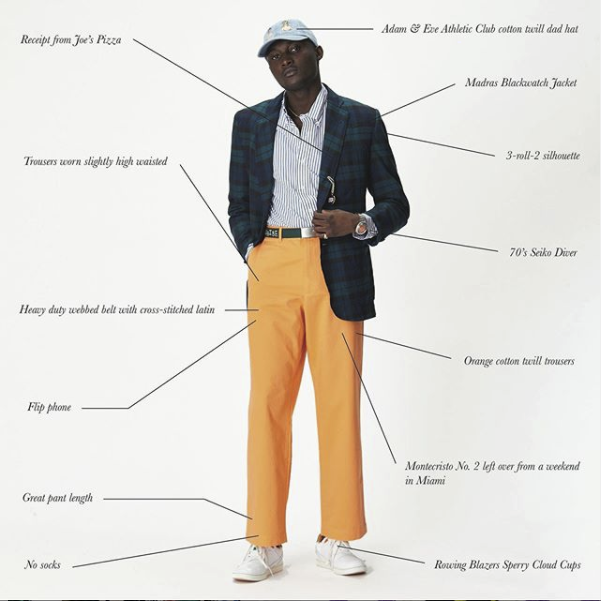

Okay, I guess I did talk about what Opp and Fuhrmann's characters consumed a bit there. But "taste" and "consumerism" are pretty deeply connected, so it's not surprising that another major focus on these posters is consumerism. And this is the perfect time for it - you're on Instagram, a platform designed to sell you something (a product, a sponsorship, a lifestyle) looking at @rowingblazers or @jackcarlson. What we consume has the power to make us who we are, or who we want to be. That the aspiration is wrapped up in a wink doesn't cancel out its power - remember, ironic aspiration is still aspiration. Let's look at what Opp and Owusu's characters stand for as consumers: bagels and cream cheese; the environment; arcade games and craft beer; Joe's Pizza; vintage watches; fancy cigars; retro, low-tech tech.

As with their taste in the earlier two posters, the Rowing Blazers character's consumer identity is presented in a way we can both look down on and look up to (and sometimes both); Barcade, for example, is "low culture" entertainment, but repackaged in a quirky, hipster way, in privileged hipster places, and it also stands (as do concert tickets or a museum map) for leisure time with friends; Joe's Pizza is a tourist draw in the Village, representing down-and-dirty, old (and by "old" I mean "1970's") New York, the New York that is mostly missed by people my age, people too young to have ever lived in it ("But it was so much more authentic"); 25 Montecristo cigars cost nearly $300, while the amount donated to the bees is unspecified, but noble.

As with their taste in the earlier two posters, the Rowing Blazers character's consumer identity is presented in a way we can both look down on and look up to (and sometimes both); Barcade, for example, is "low culture" entertainment, but repackaged in a quirky, hipster way, in privileged hipster places, and it also stands (as do concert tickets or a museum map) for leisure time with friends; Joe's Pizza is a tourist draw in the Village, representing down-and-dirty, old (and by "old" I mean "1970's") New York, the New York that is mostly missed by people my age, people too young to have ever lived in it ("But it was so much more authentic"); 25 Montecristo cigars cost nearly $300, while the amount donated to the bees is unspecified, but noble.

Maybe you have a rogue airpod or some money for nature conservancy in your pocket. Maybe you listen to indie rock or go to museums. But look at yourself. Let's be honest - unless you're Cami Opp, Curtis Fuhrmann, or Gimberly Owusu(9), you aren't the person you're looking at on your screen. They're relatable, sure. And they're consumers, just like you. So what's the difference? Well, the consumers in these posters aren't just buying concert tickets - they're buying Rowing Blazers clothes, too. Wouldn't your receipt from the local House of Pizza feel a lot more youthful and irreverent if it was in the pocket of a Rowing Blazers jacket? Wouldn't your memories of your semester abroad in Prague feel a lot more meaningful, in a Wes Anderson kind of way, if they were housed in a Rowing Blazers dad hat? These posters say they would be. And these clothes are pretty irresistible - not only are they cute and cool, but they're made in America, they're ironic and irreverent, they're youthful! Wearing these clothes says that you stand for good things, like the vitality of "prep as an ideal" as opposed to "prep as a signal of wealth."(10)

By juxtaposing the taste, the consumerism, and the clothes, the posters make an explicit argument, the oldest one in the book: buy Rowing Blazers and you can be one of these (constructed) people, have their (made-up) taste, live their (imaginary) lives. The addition to that normal capitalist message is that these people, these tastes, these lives, mean something more than a paycheck for Jack Carlson and his marketing team - they mean that you're doing something real in the world, you're standing for something. Buying a Lands' End windbreaker doesn't have to be consumerism - it can be you attaining a more meaningful, substantive, real life. Except, of course, you can't attain it, because these people are models, and you aren't. I told you to remember some things earlier, so let's unpack them now:

- Cami Opp's VW driver is absent-minded and klutzy. Take a quick look back at Opp, who is a professional fashion model. She is blonde, thin, and tall, with a symmetrical face and clear skin, fitting the beauty standard of the fashion world pretty well.(11) Her character is awkward and a bit dorky, with her weird VW and her museum map, but she also stands confidently, staring you in the eyes, wearing the heck out of her clothes. She is an example of imperfect perfection, or perfect imperfection - either an unattainable ideal wrapped in the veneer of attainability, or an attainable reality, the idealization of which places it out of our reach. Sure, Opp's fun shirt woman is human, but in a "the stars are just like us" kind of way. In the end, the relatable humanity of these characters is a reinforcement of the old ideals - wealth, privilege - rather than the new ones - inclusivity, rebellion - Chambers celebrates in his post.

- Curtis Fuhrmann's Francophile is bashful and had a crush on Mireille. Now, I'm not making an argument that this was intentional on Rowing Blazers's part, so disclaimer that I'm going out on a bit of a limb here, but Curtis stands with his head down. The juxtaposition of these two posters is interesting when you think about their gaze, and ours - Opp looks us in the eyes, not able to hide anything from us, while Curtis looks down, not challenging us with his masculinity, even allowing us to potentially replace his face with our own. But plenty of the male posters feature the models looking up - so draw your own conclusions. The Mireille thing is a bit more solid. French in Action's depiction of Mireille has been criticized as overly sexualized, with the camera lingering on her braless breasts or her bare legs; the accompanying exercise in one episode is to pick up a "pretty girl" in a park. A product of its time and place for sure, but still a time and place for which this poster is evoking some nostalgia. Opp is blonde; so is almost every woman wearing Rowing Blazers on their Instagram account (oh, look, there's Mireille!). I'm not saying Rowing Blazers is reinforcing sexism, misogyny, or exclusionary beauty standards on purpose. But they aren't not doing it on purpose either, and that kind of lazy falling into the same old same old can be troubling in ways I'll get into in the next section.

Now, you may say that this is just branding and marketing, and that it's unfair to pick it apart like this. I'd say that, well, you're right - not only is it just branding and marketing, something every company has to do to succeed, but lots of companies are doing way worse things in the name of simple advertising. Aren't they? Well, I'm not sure. Think about Patagonia for a moment: Patagonia puts a ton of resources and marketing towards supporting sustainability and the environment, so many that the former director of the Bureau of Land Management under Obama describes the company as "a group of avid environmentalists who just happen to sell coats.” It's a great cause, and Patagonia has stood by its environmental message for decades as other companies have paid lip service to sustainability. However, as Sapna Maheshwari wrote earlier this year for the New York Times, "The privately held brand sells roughly $1 billion in soft fleeces and camping gear every year while decrying rampant consumerism." In a way, and despite the fact that the world would be a better place if every company cared as much about our environment as Patagonia, or about social justice as much as Ben & Jerry's, any company which uses these appeals to something greater and nobler as a way to sell product is deserving of some suspicion. Like Patagonia's or Ben & Jerrys's conflict between their mission as a business and their message as a brand, what makes the Rowing Blazers posters worth examining to me is the way that it complicates, and even undercuts, the brand's commendable messaging on core principles like inclusion or clothing sustainability and quality.

The Real Thing

Chambers doesn't admire ironic prep just for irony's sake - he admires it because it does something real in reclaiming and repurposing a style in a way that speaks to our social and ethical concerns. All of these positions I've described - irreverence and rebellion against the establishment, a commitment to high-quality domestic manufacturing, inclusivity and social justice - are the sincere underpinnings of their ironic prep aesthetic. Rowing Blazers identifies itself with this marriage of irony and sincerity on the "About" page of its website: "At Rowing Blazers, we believe in the classics. But our approach to the classics is anything but stuffy; it’s youthful, inclusive, irreverent - and a little ironic. We can’t stand pretentiousness, but we do love being authentic and genuine."

In an email exchange in early 2019, Carlson told me,

At the end of the day, Rowing Blazers is a brand dedicated to the classics. But while for most people, classic has connotations of stuffiness and buttoned-up exclusivity, for me it means youthful, cool, evergreen, even rebellious. Sometimes there is a backlash against certain things we do, usually from people who don't understand us, or even understand what exactly they are complaining out, in the first place.The ironic prep aesthetic allows Rowing Blazers to cut through the phoniness of the establishment and show you the youthful, inclusive, irreverent reality of prep today. And this has been the party line on Rowing Blazers - that Rowing Blazers is saving prep by making it youthful, inclusive, and irreverent. "Preppy clothing should have reached its apogee with the #menswear movement, when men embraced pleated trousers, 3-roll-2 sport coats, and penny loafers," Samuel Hine wrote in a GQ piece on Carlson in 2018. "But as soon as 'Ivy Style' began to feel like costume again, prep only got stronger by ditching the tie and adapting to the current youth-led streetwear moment," an adaptation exemplified by Rowing Blazers. Ultimately, Hine writes, "Rowing Blazers’ inclusive vision feels more genuine than [just] its diverse lookbooks" - as Rowing Blazers's Instagram bio says, it's "the real thing." But if Rowing Blazers positions itself as the younger, hipper Brooks Brothers, then what does it mean when they make a replica Brooks Brothers fun shirt? Can an irreverent take on the establishment look exactly like the establishment itself? Which is the real thing?

Rowing Blazers also positions itself as a brand that cares about making clothes in America, something that establishment companies like Brooks Brothers have moved away from. In 2018, for example, Carlson said of the origins of the company,

Well, how can we bring the blazer back to its origins? How can we tell that story, not just through the book, but also through clothing? Through actually making blazers the way they’re supposed to be made?... And it was very sad for me to see that a lot of these rowing clubs that used to have their blazers made in a very traditional way are now buying jackets from China.Remember that Bishop madras jacket I mentioned earlier, the one that retails for $695? The product notes say it's 100% Indian cotton madras. I own it, and the label confirms that it's Indian madras. The jacket itself? Made in China, something not indicated anywhere on the product page. Made where in China? By whom? By being a bit disingenuous about the provenance of their products (without even noting that the jacket is "imported," a common code-word for clothes made in China), Rowing Blazers raises more questions about the ethics of their overseas manufacturing. Rowing Blazers does make a lot of products in New York, but they tend to be marquee items like the original blazers - in this way, they echo Brooks Brothers, which sets aside certain heritage pieces, like repp ties and traditional oxford-cloth button-down shirts, to be made in America while outsourcing the rest of their catalog.

Rowing Blazers positions itself as more inclusive, too. That GQ profile tells us that Carlson "proudly relays a story from when Rowing Blazers first released rugby shirts last year, and Chicago rapper Vic Mensa was among the customers waiting in line to get into the pop-up space. 'That’s when I realized what I wanted was happening,' Carlson says." He's spoken at length about the way that Rowing Blazers has embraced female customers rather being being just a men's brand. Their lookbooks have always highlighted models of color. And in recent weeks, as the United States has been roiled by protests sparked by the murder of George Floyd, Rowing Blazers and Jack Carlson have both spoken out about social justice causes. But I believe the messaging from Rowing Blazers on inclusivity is undercut by the ways the company reinforces some problematic aspects of the fashion industry, as described in the previous section.

In that same email exchange with Carlson, I asked him about the "ideology of Rowing Blazers" - how would he describe it? He wrote, "At the end of the day, Rowing Blazers is a brand dedicated to the classics. But while for most people, classic has connotations of stuffiness and buttoned-up exclusivity, for me it means youthful, cool, evergreen, even rebellious." I think that at its core, Rowing Blazers is a brand that's doing some cool things, things I support. But that thoughtful core is wrapped in an idea of "ironic prep" that I think actually undoes some of that other, cool stuff by selling the establishment, with a lot of its problematic baggage intact, as a rebellion. I followed up my ideology question by asking if there had been any ideological backlash against the brand. Carlson wrote:

A whole gang of humorless curmudgeons took to their keyboards to complain about our collaboration with J. Press and how it was a violation of their previous "Ivy style." The irony, of course, is that most of these trolls didn't attend an Ivy league college or anything like it; many of them wear Chinese-made pants; and it is entirely lost on all of them that what they call "Ivy style" was rebelliously casual, colorful, youthful, and irreverent when it began. But in all cases, it is usually the interlopers, rattled by their own insecurities, who are the most vocal and reactionary. It's like in Downton Abbey: the servants are the most radically conservative, usually about the things that really matter the least.No brand in the Ivy/prep sphere has been so successful as Rowing Blazers at turning their COVID-19 masks into must-wear items (you don't need it, you want it). They sell out repeatedly, and I see them all over Instagram. In fact, Lisa Birnbach recently shouted out Rowing Blazers while wearing one of their masks (she has at least three). Birnbach's Official Preppy Handbook taught looked-down-upon servants how to dress in Lord and Lady Grantham's clothes, and then got them to look down their own noses at the other, less pink and green servants. Carlson is making a fair point - his brand has come in for a huge amount of unfounded, reactionary criticism, often because of its commitment to inclusion, which, while problematic, is still real and valuable. But it's worth noting that he phrases that point in terms of looking down his nose - at people he deems humorless, people who didn't go to an Ivy League and so can't have a say in the style, people who buy clothes made in China (though he doesn't mean the ones sold by Rowing Blazers, I suspect). At the servants, who he casts as conservative and consumed with petty details, unlike the uber-privileged Granthams, who have the leisure and resources to look fabulous and, say, work for the Red Cross instead of dying in some mud. Carlson is right to champion youth, rebellion, irony, and irreverence in his effort to help the style he loves survive. It's just too bad that so much of how he does it looks like the exact opposite. On Instagram, Birnbach wrote, "Thank you @jackcarlson of @rowingblazers for my collection of crisp, cool, and lightweight masks! They go with everything I wear. (Obviously)." Well, yes, obviously. Perhaps, in the end, an insider recognizes another insider. Perhaps, in the end, punches hurt no matter in which direction they're thrown.

NOTES

(1)Interview by the author. A real, sincere thank you to Jack Carlson for taking the time to candidly answer some nobody on the internet. I hope you read to the part where I say I like Rowing Blazers a lot, Jack!

(2)Not a real journal. Yet.

(3)He's on page 163. There's Waldo!

(4) In a 2019 email to me, Carlson wrote about the challenges of wearing preppy clothing in a world that views them as signs of conservatism:

Well, there are always going to be people who see what they want to see, feel how they want to feel. And a lot of people want some excuse to feel angry, so they can look at our clothing, or at any 'traditional men's clothing," and see privilege, power, white America, etc. But in general, I find that's not what people see when they see our clothing, and the more informed someone is, the less likely they are to think that way. The rugby shirt, the blazer, the dad hat - the categories for which we are most well known, most of which are "classic" - all have a rich histories in hip-hop, streetwear, punk, normcore, and a whole variety of other cultural movements.(5)When your centennial daughter wears a dad hat or dad sneakers, she is making fun of you, her literal dad, but she is also becoming Dad™️, a stylized representation of patriarchal power. She undermines that power by reframing it ironically, but that doesn't mean it isn't also still literal power - it's just inverted it so that she can hold it over you.

(6)And, most likely, J. Press and Polo, at this point. However, both of these companies were started by Jews who managed to observe WASP culture from the inside, Jacobi Press in New Haven and Ralph Lauren at Brooks Brothers, which is huge when you think about the cultural meaning of these clothes.

(7)There's a fairly neat parallel here with the concept of "parasocial relationships," a term coined by anthropologist Donald Horton and sociologist R. Richard Wohl in 1956 to describe a "seeming face-to-face relationship between spectator and performer." While Horton and Wohl were describing these relationships in the context of television, the concept has been revisited recently due to the popularity of YouTube vloggers and Instagram personalities who use their cameras to build deep relationships with their viewers, which they then leverage to sell stuff to those viewers. Instead of convincing a viewer that the performer is their friend, however, the Rowing Blazers posters are convincing a customer that the performer is the customer herself.

(8)I want to emphasize quickly that Rowing Blazers uses more models than the ones in these posters, specifically on their website and in their lookbooks. However, I am focusing on these posters, as I said, because they are representations of you, the Rowing Blazers customer, rather than simply being models in a catalog or an online shop.

(9)Not to get too deep into this, but Opp, who has an Instagram account, is tagged in her posters that appear on the @rowingblazers and @jackcarlson accounts. Gimberly Owusu, the Black male model in the posters, is never identified in tags or captions (he does not have an active/public Instagram presence). However, it's important to note that the flagship poster featuring Owusu is called the "Gimberly" poster on the Rowing Blazers website.

(10) How slippery what "prep as an ideal" really stands for is is illustrated by the fact that I was just able to describe it as simply standing for the fact that it stands for something, and I bet you didn't even notice until you read this footnote. Isn't this fun?

(11)Cami Opp is not evil for having clear skin and a symmetrical face! If anyone is evil, it's Rowing Blazers, for hiring her (and, to be clear, I'm not saying that either - just that the brand, for all its obvious commitment to inclusion, still falls into some problematic habits of the fashion world in a way that can't help undermining that same commitment). And as a vocal, out member of the LGBTQ+ community and someone who has pushed back against some toxic aspects of modeling, she stands for good things. But her appearance is still relevant to my analysis, because, like it or not, it plays into some stuff about marketing. Sorry, Cami - it's not personal!